The prospect of an Ashes series between an overworked England and an underprepared Australia, has the potential to produce some appalling cricket that I’m not sure I want to watch.

England are currently plagued by injury and poor form with the bat. With each week, another fast bowler goes down and every other week, a new top-order batsman gets called-up, or recalled.

Like many supporters, each chop or change is met with the phrase: “Well, it can’t be any worse, right?”

It’s impossible to settle a team which doesn’t have the quality to succeed, but with the fixtures the way they are, matches just keep on coming and there’s no time to think. It feels like England are on a treadmill that keeps getting quicker.

While England can’t catch their breath, Australia has been metaphorically sitting on the sofa, not doing very much [other than losing, of course].

Australia last played a Test match at the start of 2021 against India at home. And they lost that series – after brilliance from India’s third string Virat Kohli-less team.

Since then, they lost a T20 series to New Zealand, lost a T20 series to West Indies, narrowly beat the Windies in an ODI series, and then lost to Bangladesh, 4-1.

To say they are lacking form in limited overs would be generous, and of course, they are also going through a tumultuous period with their coach, Justin Langer.

They are in many ways just as scrambled as England.

Joe Root, I mean England, on the other hand defeated a weak Sri Lankan side in a Test series, before being destroyed by in India in all formats. They were outplayed by New Zealand, and now they are being subjected to another mauling by India, in Tests.

I am not even bothering counting the Sri Lanka and Pakistan ODI series wins, as they were such a poor quality opponents.

What is clear, is whether overworked or underprepared, the quality in both sides is lacking.

Regardless of how good the seam attack England possess is, only one batsman is capable of scoring serious runs, so they rarely get in a winning position.

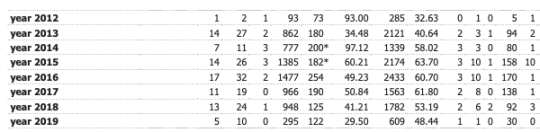

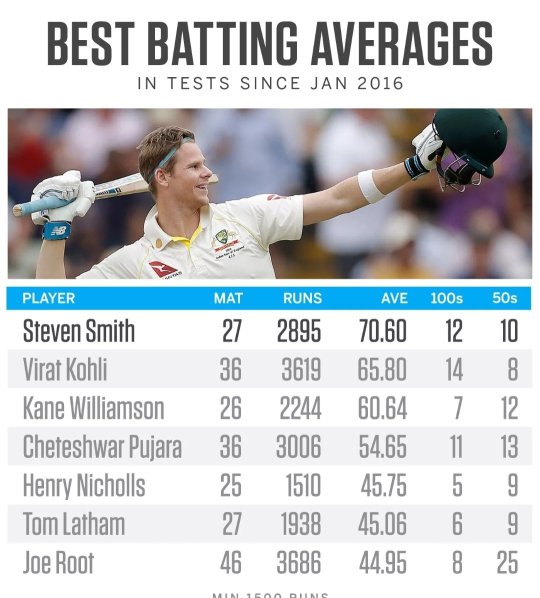

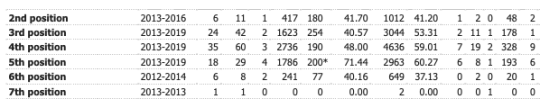

For Australia, it is somewhat a similar story, with Steve Smith and Marnus Labuschagne the only batsmen to register tons this calendar year. The previous year, only Marnus and David Warner got a ton.

It’s no surprise that Smith and Marnus were not involved in Australia’s limited overs misery this year, or it would probably have gone another way.

While England can barely get a break, the first Test cricket Australia will play after their loss to India, will be the Ashes. The next time they play any cricket, will be in October, at the World T20. They are being starved of cricket.

By the time the Ashes comes around, England would have played India in nine Tests, and both teams would have also participated in the T20 World Cup, and some players, probably the IPL too. England also have a tour to Pakistan.

The cricket is just never ending, and many players are going to be physically shattered, and probably damaged in terms of mental health also, if living in ‘bubbles’, or under restrictions.

After the last two years, having too much sport is not something one should complain about.

But frankly, I won’t be relishing getting up in the middle of the night to watch Dom Sibley and Rory Burns trigger a collapse. I don’t want to see the moment Jimmy Anderson goes off injured after bowling 2.3 overs. I have no interest also, in seeing Steve Smith score hundreds and hundreds of runs against Craig Overton and Sam Curran.

While England have a renewed and welcome focus on white ball cricket, it’s starting to be to the detriment of the Test side. The side used to think ahead and plan. Now it doesn’t have that luxury.

It has to keep going on the treadmill, until it falls off.

Well, I don’t really want to watch this cash cow be milked anymore.

The Ashes won’t have balance, quality or be entertaining – and fans deserve better.